Wine labels are not indicative of a wine’s naturalness

Why is the emphasis on labels and not on agricultural practices?

Natural wine labels have become just that, a symbol of alternative winemaking. It almost seems as though the label somehow gives a pass to be welcomed to the natural wine community. A fun, brightly colored, artistic label placed next to a traditional château and script label is obviously going to have consumers stop in their tracks and reach for the ‘fun bottle.’ For my non-wine professional friends, the label is one of the first things they boast about when bringing over a bottle for dinner. Like a girl bragging about a dress with pockets. We are taught not to judge a book by its cover, but in fact, isn’t that what covers are for? There needs to be a balance between art and context. The fun label will make me pull it off the shelf, but once I turn over bottle and see the back label, I still want to see the producer and the viticulural practices.

Here are a few producers, and their labels, that got me thinking.

Marchesi di Ravarino is a sparkling wine producer in Emillia-Romagna. See how I hesitated to say that it was Lambrusco? I remember watching Somebody Feed Phil, a silly travel show on Netflix. During the pandemic, that was all I had; movies, and TV shows about Italy. In this episode, Phil visited Modena, and toured the city with legendary chef Massimo Bottura. There was a scene where Massimo ordered Lambrusco rosé and in that moment, I thought, if it’s good enough for one of the world’s top chefs, it’s definitely good enough for me. Years went by and I never found a sparkling Lambrusco rosé on the shelf or in a restaurant, anywhere; until I went to Modena. (I should mention that sparkling rosé is one of my favorite things in the world). A year after my first bottle, I went to a wine tasting in Milano put on by the Slow Wine Coalition and met the winemaker, Nicola. I know we are not supposed to judge a book by it’s cover, or in this case, a wine by it’s label. I know enough that a wine label has nothing to do with its naturalness. But I was intrigued either way.

Nicola hosted me at the winery so I could learn more about his story and of course taste the wines at the source. We drank baby Lambrusco (wine that was harvested not a month prior) from the tank, and ate Parmigiano Reggiano drizzled on top, Aceto Balsamico that was aged for who knows how long (in the best way possible). What really struck me was the new labels they were using for their wines. Lambrusco is stereotypically recognized as a sweet, mass-produced wine, not to mention cheap in price. Marchesi di Ravarino wines were the opposite of that. These are naturally made wines, the grapes were farmed organically, and they taste great. They aren’t too funky, polarizing, or acidic like other poorly natural wines tend to taste. Funky labels do not mean funky wine, but in Marchesi di Ravarino’s case the labels are helping them stand out in the market, and they can be visually seen as an alternative to the cheap, mass-produced Lambrusco of the past.

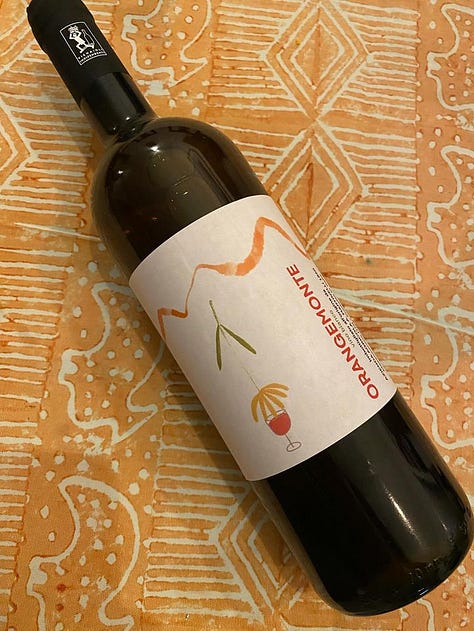

Let’s look at another example. Cantina A. Martinelli is a historic winery in Trentino. Over the last decade the family restored the historic winery and property to a full functioning winery and event space. Gorgeous and unique is an understatement. They make a full line-up of Teroldego, many of which satisfy the requirements of the DOC, each bottle highlights the grape in a different way, even in rosé. The labels are traditional and for the winery and history of the region, frankly, makes sense. In addition to the core line-up, there is also a new line of natural wines being made on site. Orangemonte and Biancomonte are both wines made of Souvingner Gris, the Orangemonte is aged on the skins lending to its orange hue, and Biancomonte is a white wine. The labels make it clear that these are natural selections. That doesn’t mean their other wines are conventional wines, they are not. They do not adhere to all principles natural wine producers follow, in the case of Teroldego wines, they use selected yeasts and age some wines in new oak barrels, but Teroldego is an intense full-bodied red, oak aging makes sense for this style. The important thing is that they farm the grapes organically, hand-harvest them and are a family-owned winery, not a brand. They are also heavily involved with the Italian Federation of Independent Winegrowers (FIVI) and literally rebuilt and restored a cantina and property from the 1800s.

Another great example. Tenuta San Marcello is a winery and agritourismo in Jesi, Marche; a small region on the Adriatic coast. They make a line of natural wines with alternative labels, and wines that can sit on the shelf next to conventional wines that meet the requirement of the DOC1 for Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi and Lacrima di Morro d’Alba. In this case you can’t judge a book by its cover, because all four wines pictures below are technically natural wines, made with naturally occurring yeasts, minimal intervention in the cellar and, of course the farming is organic. You just have to look beyond the label.

I’ll give you one more for good measure. Another winery called Corte Bravi is making classic DOC and DOCG wines, naturally. From their Valpolicella Classico to Amarone della Valpollicella. By first glance they don’t look like the crazy-labeled, cloudy natural wines that the media often depicts. But they use local indigenous yeasts, and have less than 30 mg/liter of sulphites.2 They also make a line of wines that fall into the category of natural wines from a fun label perspective. Bocia and Vivace play tribute to the playful spirit of these wines and their family members' personalities. Side by side, you would think that one was a conventional wine, one was a natural, but again, all their wines are natural.

There is a way to differentiate between natural wines that are following a trend, and natural wines made right. It’s called trial and error, research and asking questions. Understandable that not all wine drinkers can differentiate flaws from “naturalness.” But this is part of the problem. My advice, do your own research and don’t be afraid to say that you don’t like something. Odds are you are not wrong. I don’t talk about or write about the wines I don’t like or are too polarizing for me, but they are out there. Some are wines from producers that get a lot of hype in the wine world. At first I was too nervous to speak my mind at wine events and tastings because I thought that I was in the wrong for not being able to appreciate these “nuanced” flavors. Now I know a little better. I am on a mission to teach remind others that natural wine does not always look like fresh canteloupe juice. Natural wine has the ability to age. Natural wine can come in any bottle shape and label. Natural wine comes from responsible farming practices.

I guess I’ll leave with you all with the question, ‘Why is the emphasis on labels and not on agricultural practices?’

“D.O.C. stands for Denominazione di Origine Controllata (literally Controlled Designation of Origin). It is a certification applied to Italian wines that, under the law, have distinctive features of superior quality, determined by the grape varietal and the production area as well as the techniques for processing and aging” (La Cucina Italiana).

Love tenuta San Marcello! Just tasted the wines at the natural wine fair in Rome